A Perfect World…

In a perfect world, the BBWAA elect Keith Hernandez in the late 90s into the hall of fame. But also in that same ‘perfect’ world Bill Buckner never looses sight of the ball in game six and the Red Sox end up winning the 1986 World Series. Baseball since the dawn of its existence has been something of an anomaly. It’s going to have moments leaving you scratch your head in confusion wondering how the hell Bartolo Colon hit a home run in his 19th year of baseball at age 42 or how Randy Johnson’s 100 MPH fastball killed a bird in seconds. The raw, chaotic emotions are what define the unpredictability of baseball. But what doesn’t belong in that chaos is when the Hall of Fame snubs a player who so clearly deserves admission — only to leave them to fade off the ballot and into obscurity. None other than Keith Hernandez deserves his flowers today after being disrespected from Major League Baseball as one of the best first baseman to play the game.

In baseball, the term ‘Wins Above Replacement,’ or known as WAR for short, is a saber metrics statistic that quantifies the number of wins the player brings compared to a replacement-level or bench player. We will be using WAR as the main argument for today as the reason why Keith Hernandez should qualify for the Hall of Fame.

Who was Keith Hernandez

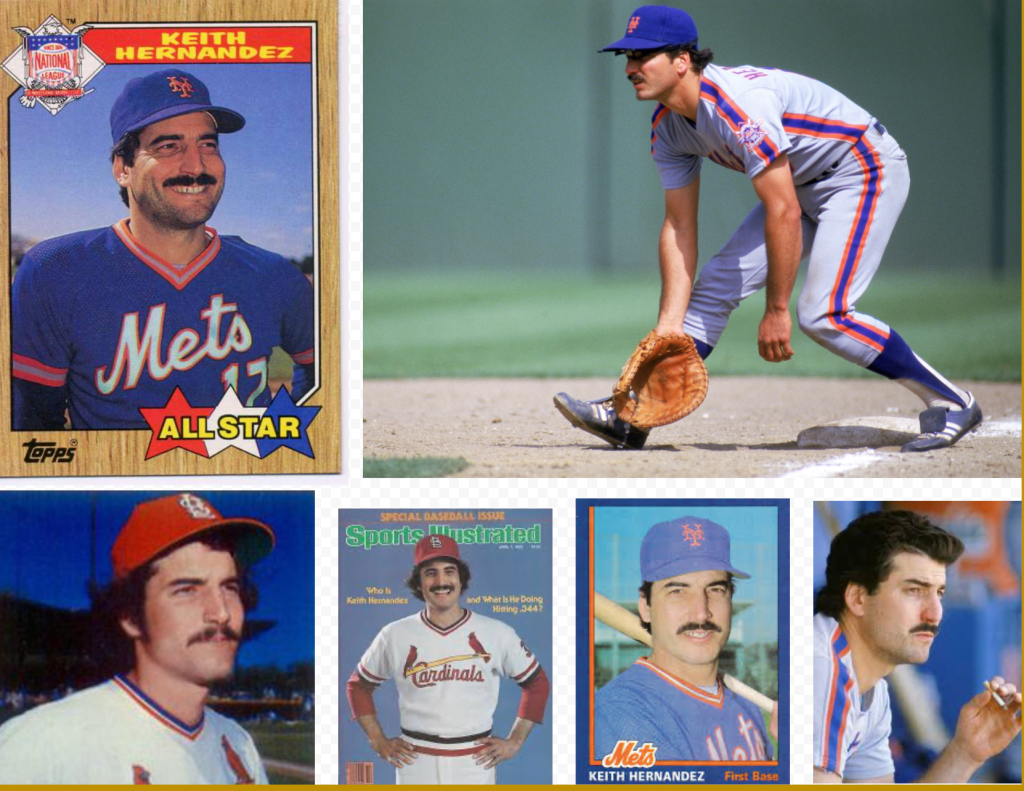

In modern Hall of Fame voting, accolades don’t carry as much weight as they once did in determining a player’s worthiness for induction. However in order to establish the quality of talent the player brings accolades are an important first threshold to discuss.Through 17 seasons, Keith Hernandez accumulated 60.3 WAR, recorded over 2,000 hits, and earned an impressive 11 Gold Gloves — the most ever by a first baseman. He was also the 1979 National League MVP, five-time All-Star, batting title winner, two-time Silver Slugger, and a World Series champion with both the Cardinals and Mets during the 1980s. All these awards won make you question the minimal recognition he received from the BBWAA, denying the legitimacy of one of the best to ever play the game.

Lets Talk Logistics

However in order for a player to remain eligible for the ballot they must retain at least 5 percent of votes per year and unfortunately for him he did not see the writers minimum. 2004 was the ninth and last year Hernandez was on the ballot with his final 4.3% of the votes not making the cut to stay on. He does have a chance to make the hall of fame again via the Eras Committee which is set for their next ballot selection later this year.

Let’s talk logistics. Even though WAR is not the end all be all for deciding baseball immortality. It is with strong recognition of many baseball writers that a player that stands between 60-70 career wins above replacement is in healthy place to enter, given the reasoning, Keith Hernandez falls right into a strong rank between his competitors for a spot of baseball immortality.

While the typical threshold may be in that range, there are several Hall of Famers who were granted admission into Cooperstown with less than what Keith Hernandez totaled in his 17 years. Another Mets legend, Mike Piazza, recorded 59.5 WAR on his way to a Hall of Fame selection in 2016. Even after finishing with more All-Star nods and a Rookie of the Year award, he still ended up with less WAR than Hernandez — who was more of a defensive-minded player. Or look at Joe Mauer, a catcher, who’s career is similar to Hernandez and made it to the hall of fame with 55.6 WAR.

WAR is not the end all be all for HOF Voting

Both Mike Piazza and Joe Mauer played catcher — arguably the most important defensive position on the diamond — and both recorded fewer wins above replacement than Hernandez. A lot of that stems from the fact that catchers don’t play every day. They have less time on the field, fewer at-bats, and their defensive skills often aren’t fully captured by traditional WAR metrics. That’s why even elite catchers post lower WAR than first basemen — but that doesn’t mean they were less valuable.

The Grit and Prowess of a Leader

But all of a sudden, they’re now seen as more qualified to be Hall of Famers than Keith Hernandez — a guy who played 17 years, every day, and was the captain of the Mets. I understand that some of the statistics may not look flashy on paper, but as the years go on, the argument only grows stronger for why Hernandez deserves a spot in the Hall. His consistency, leadership, and impact on the game go far beyond what a spreadsheet can measure.

From 1974 to 1990, Keith Hernandez played across three decades of baseball, with his best season coming in 1979 when he racked up 7.6 WAR. That year, he led the league with 48 doubles and 116 runs, collecting 210 hits, 105 RBIs, and batting .344. In six of his 17 seasons, he finished with a batting average over .300 — and in another five, he was right there, just below that mark. He’s always been a threat both at the plate and in the field, yet somehow his Hall of Fame argument gets shut down almost instantly. It’s like people forget how consistent and complete his game truly was.

He might not have had as much power as Hank Greenberg did with the 1920s Tigers — who put up 55.3 WAR in just 13 seasons and made his mark as a home run hitter, blasting a career-high 58 bombs in 1938 — but if Greenberg can get in as an important part of baseball’s history, then Keith Hernandez deserves a seat at the table too. And most recently, Fred McGriff was voted into the Hall of Fame through the ERA Committee ballot. Don’t get me wrong — great for him. I’m not saying he doesn’t deserve a spot. But when there have been so many significant snubs over the years, it’s frustrating to see a guy with subpar stats make it in just because he was “good enough” for long enough.

McGriff racked up over 2,400 hits and 400+ home runs in 19 years — that’s impressive, no doubt. But to be brought in as a first baseman before Keith Hernandez? That’s blasphemous. Especially when you consider how hard it is to be an elite defensive first baseman. If you’re not elite — not game-changing — why should you be rewarded with a Hall of Fame ticket? Hernandez gave the game blood, sweat, and tears for nearly two decades. To leave him on the outside while ushering in players based on longevity alone just doesn’t sit right.

The Argument is Flawed

The whole reason for this silly argument is the same argument that held back Pete Rose from entering the hall of fame or Shoeless Joe Jackson. It’s the same argument why it took so long for Dwight Gooden and Darryl Strawberry to be recognized by the Mets hall of fame. The sole argument the Baseball Writers Association uses is focusing on their off the field antics to justify keeping them these accomplished players from the hall of fame.

The Turning Point

I wholeheartedly believe baseball has taken the wrong approach in deciding who should and who shouldn’t be allowed in the Hall of Fame. Nowhere in the Hall of Fame manual does it state that a player should be denied entry based on activities off the field. It is one thing for the league to condemn the behavior, but at the end of the day players are human. Dedicating all these years of training and being the best version of themselves on the field doesn’t mean they aren’t allowed to enjoy themselves as they please off the field. However, it becomes challenging when that behavior bleeds into on-field expectations.

Keith Hernandez was one of many players who used cocaine, and he might have been one of the leading people most affected by this.

Baseball in the 1980s was seen as a wild and unorthodox time of clubbing culture and cocaine fiascos. It was not abnormal for players to engage in the substance, and at the time if you were winning baseball games no one batted an eye if you did it during games. During this time in baseball cocaine consumption was at an all-time high. Before the Pittsburgh drug trials, there was no official penalty enforced since it did not violate MLB policy at the time.

The issues at hand are minuscule and have no relation to the performance and quality of the player. They’re strictly in relation to off-the-field antics. Specifically for Keith Hernandez, he had a history of using stimulants, especially methamphetamines, but like many players in the 1980s, that didn’t stop them from being highly productive. I mean, Dock Ellis, the famous Pirates pitcher, was on a tab of LSD when he threw a no-hitter, yet that didn’t tarnish his legacy as an elite individual. It’s disheartening that with all the accolades Keith Hernandez left on his mantel, people will remember him more for his substance use disorder than for being a terrific first baseman.

In September of 1985, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that Major League Baseball was beginning to crack down on the cocaine epidemic. Several players, both current and former members of the Pittsburgh Pirates, as well as other notable stars, were called into a Pittsburgh grand jury to provide testimony about their experiences with the substance. Keith Hernandez was among them.

He testified to the grand jury stating his claim that over 40% of the MLB had used it across the 1980s, later testifying under oath he never distributed it. Keith alongside six of the prolonger users suspended and handed commity servicPlayers were suspended for one year of baseball unless they gave up 10% of their salary to drug-abuse programs, submitted to random drug testing, and contributed 100 hours of drug-related community service. Keith Hernandez was among those linked to cocaine use, which became public during the Pittsburgh drug trials of 1985. Under oath, he never admitted to distributing the drug, though it was said he had and was even accused of supplying it to other players. At first, a season-long suspension hung over his head, but like others, he avoided it by agreeing to fines, drug testing, and community service. To this day, and for the rest of his career after that point, he never touched the substance again — and that says something.

A Dedicated Warrior

fter national scrutiny and an unprecedented year that saw Hernandez admit to never distributing cocaine, he followed it up with arguably his best season: a 5.5 WAR year, a .310 batting average, 94 walks, 83 RBIs, a .446 slugging percentage, and a 140 OPS+ — all while helping bring a second World Series title to Queens.

Keith not only rebounded, he thrived under the media pressure and on the postseason stage in the National League. And so who cares about Keith’s past? That doesn’t mean anything to those who truly care — the fans. So why does it matter? Regardless of anything, one thing is for sure: Keith was always going to be the best version of himself, both in St. Louis and in New York. He played with strong fundamentals and great leadership, and those two skills became the centerpiece of Keith’s time with the Mets. From 1983–1989, Keith was the voice and icon for Queens faithful.

One of the Best

On his Baseball Reference page, Keith Hernandez is ranked as the 15th-best first baseman of all time by WAR. The average WAR for Hall of Fame first basemen is around 61, and with Hernandez sitting at 60.4, he’s right there. His JAWS score, which compares both career and peak WAR, sits at 50.8, with a peak WAR (WAR7) of 41.2. Defensively, he’s elite — arguably the best glove at the position in the modern era — but when you stack him against other Hall of Fame first basemen, his power numbers and traditional metrics fall below the typical threshold.

First base has always been a tricky position for Hall voters. It’s seen as the “easiest” defensively, and unless a player puts up a prolific power profile like a Pete Alonso or Paul Goldschmidt, they get overlooked. But all I have to ask is: if a guy like Keith Hernandez can have a nationally recognized season — win an MVP, rack up 11 Gold Gloves, and lead his teams to a World Series — why can’t he be nationally recognized for a lifetime of excellence? Why can’t that same impact be honored with a plaque in Cooperstown?

Final Remarks

To repping the “C” on his uniform to bestowing the honor of the second world championship for the franchise, Keith has always been fondly remembered not just for his time with the Mets but for baseball altogether. Even if he may never make it to Cooperstown, he has proven that even the greatest of players can finish short at the finish line — but that doesn’t mean their success and accomplishments were for nothing. Keith’s impact on the game is beyond what words can describe. He was a dedicated warrior.

Leave a reply to De. Terry L. Jobe Cancel reply